236

236  60

60In recent years, "rhenium-doped gold" has frequently caught the industry's attention. Whenever gold shops, recyclers, or testing labs see "Re" on an XRF screen, the first thought is: "Is this rhenium again?"

Recently, we encountered a case that initially appeared to involve rhenium. After retesting, however, the truth was surprising: the gold contained no rhenium at all, but only 0.64%–4.9% germanium (Ge).

This case highlights three key questions:

1.Why does germanium appear in gold?

2.Why can XRF misread Ge as Re?

3.How does PURERAY's analyzer prevent such misidentification through curve-based applications?

1. Why Does Germanium (Ge) Appear in Gold?

Germanium is not a natural impurity. It is introduced during manufacturing.

In many hard-gold (5G gold) processes, factories add small amounts of Ge to the gold powder or intermediate alloys to make the gold:

· Lighter

· Thinner

· Harder and more rigid

· Capable of complex shapes

This element is not "fake-gold additives"but the process element intentionally added to achieve specific mechanical properties.

Why does it remain in the final product?

In theory, some Ge should evaporate or be removed during melting and refining at high temperatures.

If:

· the melting temperature is insufficient

· the duration is too short

· mixing is uneven

· remelting is incomplete

then Ge in gold products, typically ranging from 0.5% to 5%, is quite common.

In this case, the sample showed 0.64%–4.9% Ge across multiple test points—typical of residual germanium from hard-gold powder processes.

2. Why was it misidentified as Rhenium (Re) by XRF?

— The issue did not originate from the gold itself, but from the software configuration.

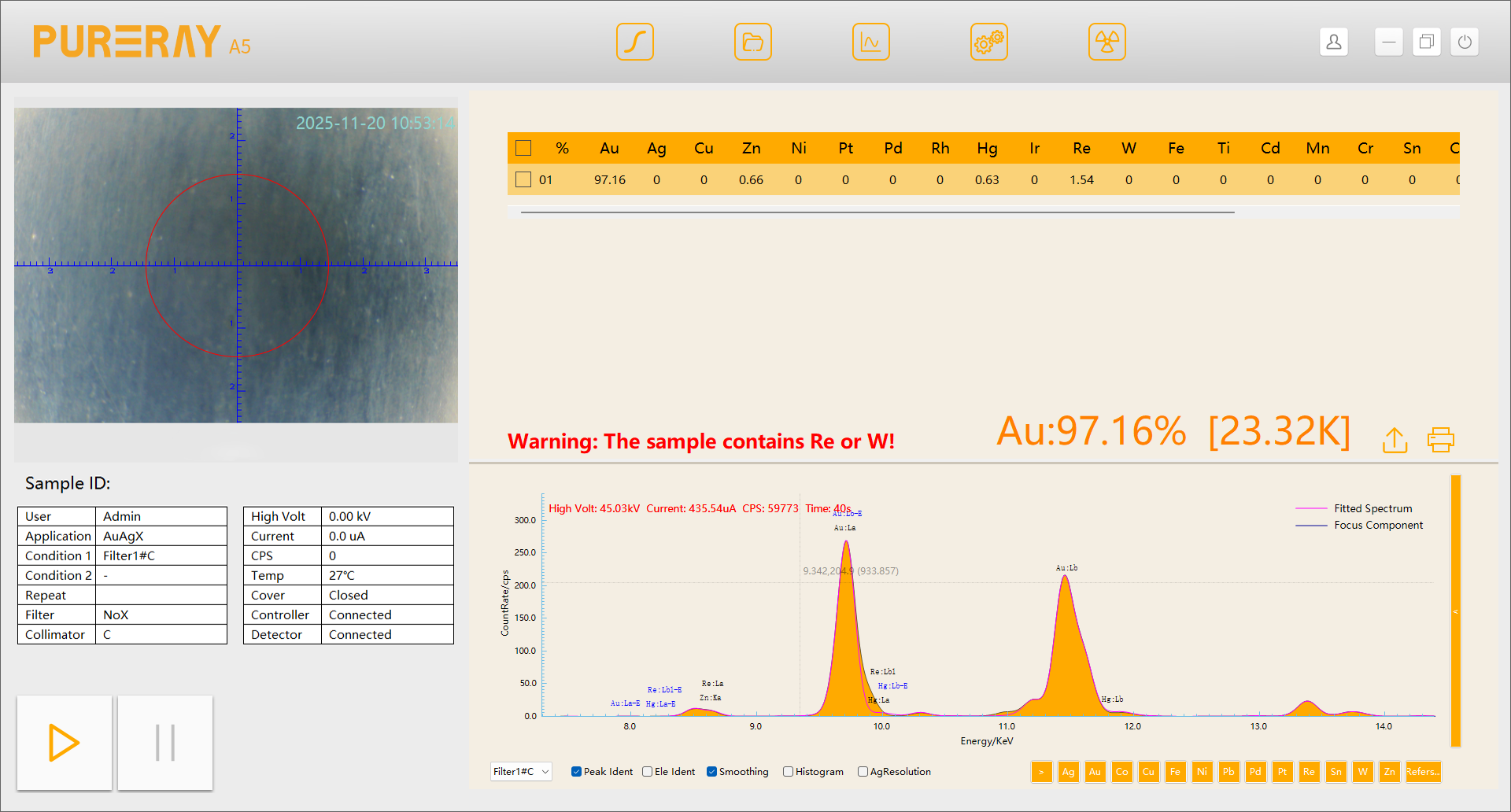

Given frequency of rhenium-related fraud, any "Re" reading naturally raises concerns.

However, in this case, the issue was not with the gold. It was with the software configuration:

The curve-based application used at the time did not include Ge in its element library.

XRF analysis is based on matching spectral peaks to predefined element models. When an element present in the sample is not included in the analytical model, the algorithm may try to interpret its peaks as those of other elements with overlapping spectral features.

In this case, that meant:

· The sample contained Ge

· Ge was not enabled in the curve-based application

· Some spectral features overlapped with Re

· The algorithm misinterpreted them as Re

In other words: that "Re" reading was caused by a missing model + spectral overlap, not by rhenium in the sample.

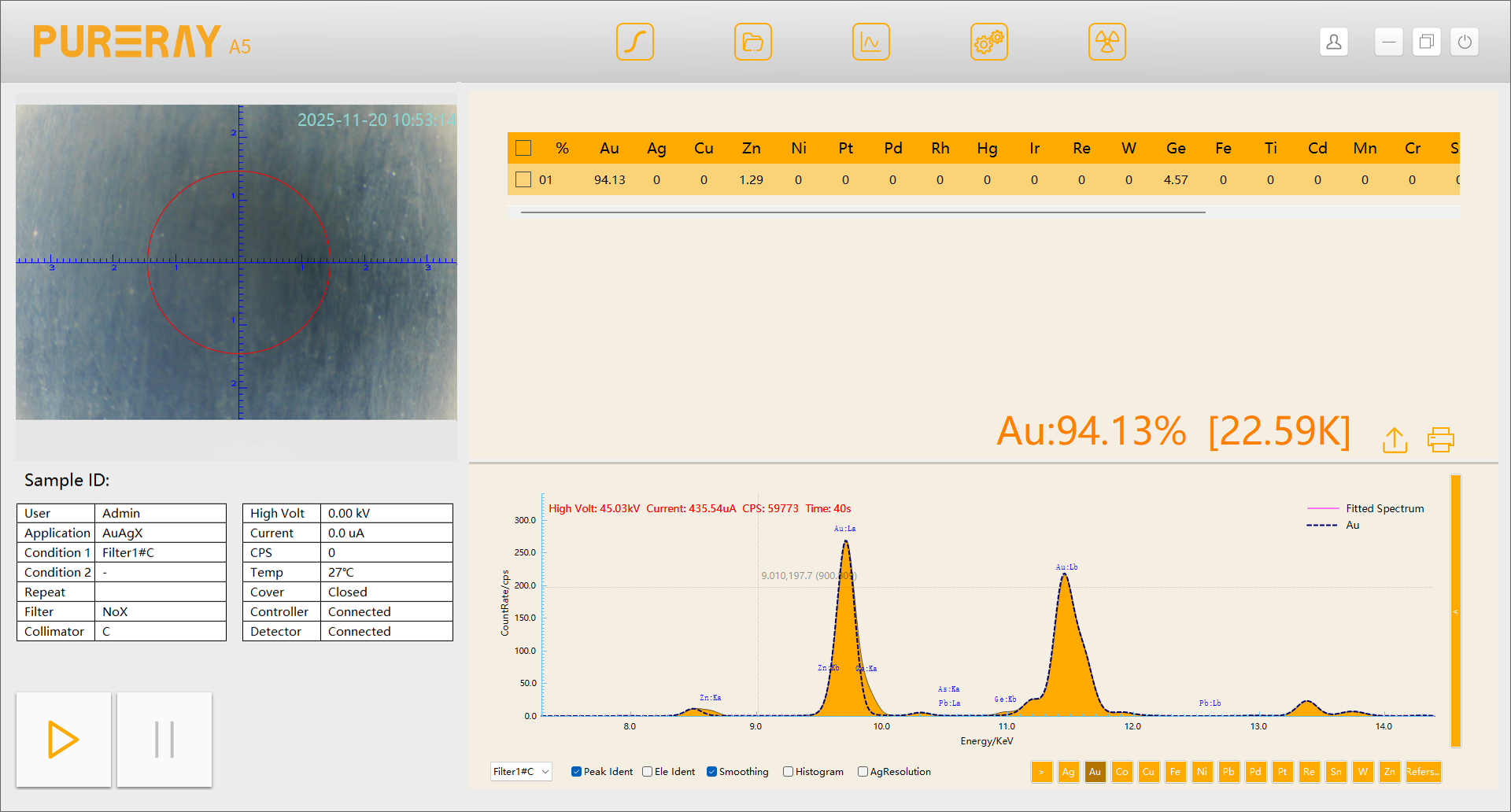

After enabling Ge in the curve-based application and retesting:

· The "Re" result disappeared

· The software correctly identified Ge

· The spectral fitting aligned perfectly

The logic behind the misidentification was clear and consistent.

3. How does PURERAY prevent misidentification?

— By enabling Ge in curve-based application so the instrument recognizes it automatically

We do not expect every user to analyze spectra manually. Gold shops and recyclers shouldn't need to memorize peak positions or energy lines.

In PURERAY's design:

Complex spectral logic should be handled by the algorithm, allowing the user to simply select the correct elements.

For the Ge vs Re issue, the solution is straightforward: enable "Germanium (Ge)" in the curve-based application.

Once enabled:

· The algorithm includes Ge in its fitting model

· It automatically distinguishes Ge peaks from Re

· It prevents “false-positive rhenium” results

· The user sees only accurate, stable readings

The user does not need to:

· Determine whether the sample truly contains Re

· Analyze spectral overlaps

· Understand K-series vs L-series peaks

All of that is handled internally by PURERAY's FP-based spectral inversion algorithm.

In short, with Ge enabled, PURERAY instruments recognize germanium correctly and avoid misreporting it as rhenium.

4. Germanium ≠ Fraud, but It Does Signal a Manufacturing Issue

It is important to clarify:

Detecting Ge does not mean "fake gold."

Instead, it reflects a process-related characteristic.

It usually means:

· Hard-gold powders or intermediate alloys were used

· Melting or remelting was incomplete

· Mixing or process control was unstable

From a testing standpoint:

· As long as the gold purity is correct, authenticity is confirmed

· Ge mainly reflects upstream process control and can be used for traceability or manufacturing optimization

Conclusion: Gold evolves, counterfeiting evolves, and testing must evolve as well.

In recent years—whether tungsten doping, rhenium doping, or new hard-gold formulas—gold has become more than a single-element material. It now carries multiple process-driven risks.

In this new situation:

· Checking gold purity alone is no longer enough

· Looking at one or two numbers is no longer enough

· The software model, element library, and algorithm matter more than ever

This "false Re, real Ge" case reinforces a clear direction:

XRF instruments must advance not only in hardware, but continuously in software and algorithm capability.

PURERAY will continue refining curve-based application, element libraries, and FP algorithms—embedding complex spectral logic into the system so frontline users only need to do one thing:

Choose the right application, enable the right elements, and let the instrument handle the rest.

As gold materials become more complex, detection should become simpler.

-

True FP Algorithm Series (part 7)“The Core of the True FP Algorithm — From Forward Modeling to Spectrum Inversion”

-

“False Rhenium, Real Germanium”: A New Risk in Gold Manufacturing

-

True FP Algorithm Series (Part 6)Application of the True FP Algorithm in Coating Thickness Detection — One Test Solving Four Major Challenges

-

-

Probe into Novel Gold-plated Jewelry2025-06-04

Probe into Novel Gold-plated Jewelry2025-06-04 -

-

XRF Secondary Programming - "Formula Editor"2025-03-23

XRF Secondary Programming - "Formula Editor"2025-03-23 -

-